Transcript

Transcript

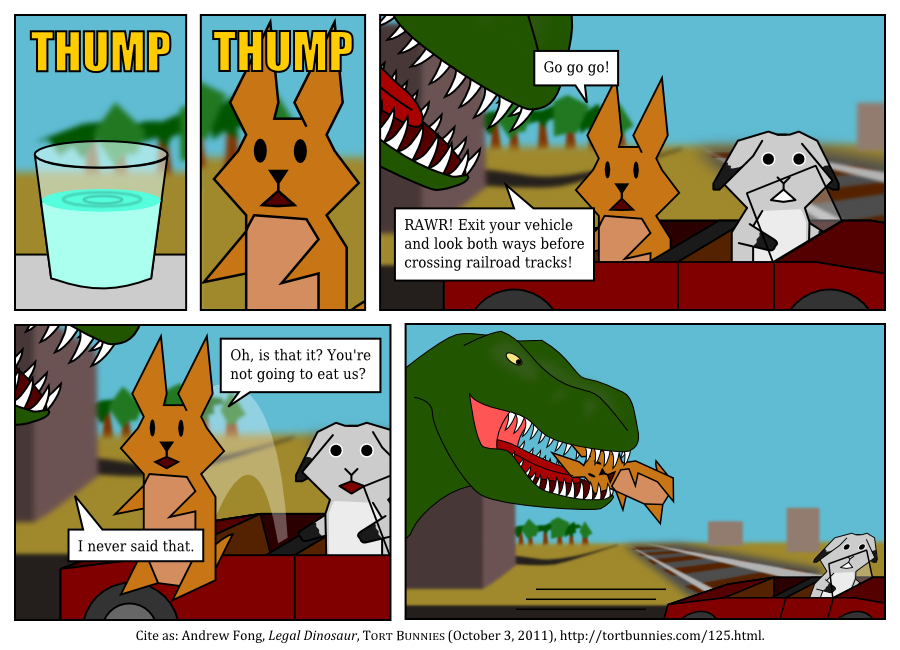

October 03, 2011. Generally speaking, every person owes a duty to exercise reasonable care towards others. The question is (1) what's reasonable, and (2) who gets to decide that? Apparently, enough people drove into trains in the 1920s that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes felt obliged to define the proper standard of care for driving across railroad tracks:

When a man goes upon a railroad track he knows that he goes to a place where he will be killed if a train comes upon him before he is clear of the track. He knows that he must stop for the train not the train stop for him. In such circumstances it seems to us that if a driver cannot be sure otherwise whether a train is dangerously near he must stop and get out of his vehicle, although obviously he will not often be required to do more than to stop and look. It seems to us that if he relies upon not hearing the train or any signal and takes no further precaution he does so at his own risk.

Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U.S. 66, 69-70 (1927). In other words, if you get hit by a train while driving, it's your own damn fault.

Unfortunately, judicial definitions of reasonableness don't age well. A jury's definition of what's reasonable does not bind future juries to decide the same way. When a judge makes that decision, however, the decision can become a reported opinion that constrains future judges. That's great for keeping the law consistent and predictable, but what seems reasonable to a 1920s Supreme Court Justice may not make sense to your average modern-day commuter (especially if the Justice didn't drive). Or as one court put it, such a decision "unlooses a legal dinosaur, which, once out, tramples twentieth century negligence law and then lumbers back to its dark cave only to await another victim." Hurst v. Union Pacific R.R. Co., 958 F.2d 1002 (1992).

Punchline blatantly borrowed from from Hark! A Vagrant. Inspiration from Jurassic Park, or as I like to call it, "Negligence with Dinosaurs".

Comments